Every day, local citizens and camera-flashing foreigners pass the pillars of the University of Tartu Main Building, not to mention thousands of students along with the lecturers. In the beginning of the 19th century, this was only a dream.

It was a dream that found its chance to become reality in 1801 when the Keiser Alexander the First finally reached a decision: the university would not be built in Miitava, Kuramaa (today we know it as the Latvian town called Jelgava), but in Tartu, Liivimaa, instead! Two years later, Johann Willhelm Krause arrived in town and went on to become the architect of the university ensemble in Tartu.

Johann Willhelm Krause (1757-1828), the architect of the University of Tartu. Photo credit: Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation

Enlightenment brought a novel conception of the university, a vision of the architecture that was suitable to the era and was widespread from Europe to the United States. In many ways, the student campuses that formed in the 19th century have become a reflection of the changes that took place in the social consciousness and inter-societal relationships, and paved the way to the development of the modern world of today. In this tumultuous rising tide, the architectural ensemble of the University of Tartu was born, one of the most genuine and best-preserved examples of a university of the Enlightenment era.

When speaking about our alma mater, we have to start from the year 1632, when the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf founded one of the four universities in the Swedish empire, then known as Academia Gustaviana, in Tartu. In the 18th century the Great Northern War forced the university to cease activities, but the university was reopened in 1802. After some disputes about where to locate the university, the new emperor of Russia, Keiser Alexander the First, conclusively designated Tartu as the location.

Johan Wilhelm Krause, the architect of the University of Tartu, was invited to Tartu by the first Rector of UT Georg Friedrich Parrot. They were close, since they were brothers in law. Krause arrived to Tartu in February 12, 1803.

Juhan Maiste, Professor of Art History at the University of Tartu, describes the architect as follows: “Krause was born and died in Dreieck – in between Bohemia, Poland, and Germany. Having lost his parents as a young man, he set out on a path of spiritual Enlightenment. He was a natural born talent, a genius of his time”.

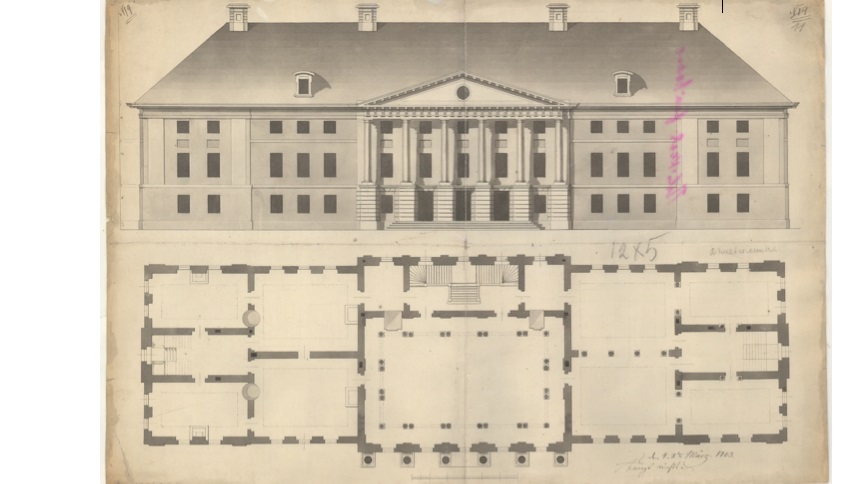

Immediately, Krause was asked to conceive schemes for the future building of the university. In just a couple of days, Krause sketched the first depiction of the forthcoming Main Building on a small, blue-grey piece of paper, and as early as on 27 April 1803 the projects and budgets of the university were confirmed – just a little over two months later.

Finding a suitable location for the Main Building was a complicated process. Both Toomemägi and the shore of the Emajõgi River were considered. But the latter was well-known to be marshy and thus unsuitable; moats and other soil-related problems were feared as well. The esplanade was also criticized for being noisy, as it was near to a large marketplace. An academic building needed peaceful surroundings.

Placing the Main Building on Toomemäe Hill wasn’t that popular an idea either, with only a single sketch left of it, as problems with the soil were highly likely and the location was too small. Its other disadvantages would include the danger of fire and slipperiness during winter.

Treasure Hidden Under the Main Entrance

Finally the decision was made to use the forecourt of the Maarja Church, as it wasn’t used for anything yet, and it had more space and a better location. To this day, the building of the university is located in the same place.

In the early spring of 1805, the detonation of the walls occupying the space began, and on 15 September 1805 the cornerstone for the main building was put into its place. It was made from an old gravestone and laid next to the main staircase of the university.

A box with some coins from the same year, as well as the chronicle of the university, including some of the most important dates, was buried under the main entrance. There was also a list of persons who were involved in the making of the building. In addition to all that, documents with data about the prices of food and materials, as well as the workers’ daily salaries, were included in the box. The most important man of this day was definitely Krause, the architect.

Building the main house was not an easy task. Graves and tombs were unearthed, layer after layer. Human bones were found under 12-13 feet. But an even more unpleasant surprise followed, when water was found from the bottom of the excavation, amid the medieval walls. Building something on the marshy valley flat of the Emajõgi River needed costly additional work and lots of manpower. Thus, everything turned out to be more expensive than initially planned.

“With the help of local master builders, carpenters, and masons from Russia, Krause spent about ten years on the building site and designed almost all of the university buildings. Being self-taught and understandably lacking the education of a professional architect, he had an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of the building arts. As an architect Krause was influenced by the great cities of Europe: Dresden, Berlin, and St. Petersburg, which he was lucky enough to see with his own eyes”, Juhan Maiste describes.

The University Times

While the buildings of the university were still being constructed, many lectures took place in the private flats of the professors, where the cathedra and auditorium benches that actually belonged to the university could be found. The official inauguration of the university took place on 31 July 1809.

At first, four faculties were located in the Main Building — law, medicine, theology, and philosophy. The Main Building also had the museum, arrest chambers, the academic court with its archive, the auditorium for learning chemistry, the room for apparatus storage and laboratory, the room for devices used by the physicists, the cabinet of minerals, as well as rooms for janitors and calefactors (heaters). Looking at the first drafts, one could spot that halls for dancing and fencing were planned to be in the Main Building as well, but probably no special rooms were built for these activities and existing ones were used instead.

“When it came to the interior design of the University Main Building, Krause recommended that white and grey paint should be used, as it was the most practical to maintain. The ceiling of the university hall should have been painted in the red colours of Hebrew sunrise. The university hall speaks of eternal beauty, harmony, and perfection”, Juhan Maiste describes Krause’s objectives when designing the interior of the Main Building.

Problems with the Local Government

Some oft-occuring troubles for the university turned out to be the uneven beginning times of lectures. In 1802, the council of the university brought up a problem with the main clock of the City Hall, as it was functioning on terms that were too vague for the learning to go as planned. The saga with the clocks continued until in 1824 a pendulum clock was installed in the Main Building, on the initiative of Friedrich Wilhelm Struve, and it has stayed there to this time. Struve promised to take care that the clock would always be set according to the actual position of the sun, and, moreover, that the clock of the City Hall would be controlled according to that of the university. Thus, Tartu was really living in accordance with the “university time”.

As the town was living in the rhythm of the university, it created tensions and disputes between the City Hall and the university. The university meant privileges, and went on to act independently from the local governors, according to its own jurisdiction. On the other hand, the powers of the town still tried to complicate matters. For example, the town refused to sell some grounds for building new roads and didn’t help at all with developing an infrastructure for the university.

Fortunately, as we know now, the University Main Building stands strong and we have a beautiful university landscape.

This article, composed by Kadri Asmer, is based on the compendium “Johann Wilhelm Krause. The University in the Athens of the Emajõgi River. Catalogue 4”, compiled by Professor Juhan Maiste and Anu Ormisson-Lahe, with the cooperation of many researchers from both Estonia and other countries. It is a voluminous study that focuses on the architecture of the University of Tartu and J.W. Krause’s output. The aforementioned compilation is the last of the four-part series dedicated to the man.

The Estonian version of this post was published in ERR Novaator.